For him, the horror of the trenches was just another kind of association with death. He was born in Northern Ireland in 1898, enjoyed a quasi-public school education in England, and then served as an officer in the first world war, where he was quite badly wounded in action. Throughout his life, “Jack” Lewis was a man tortured by the tragedies of love.

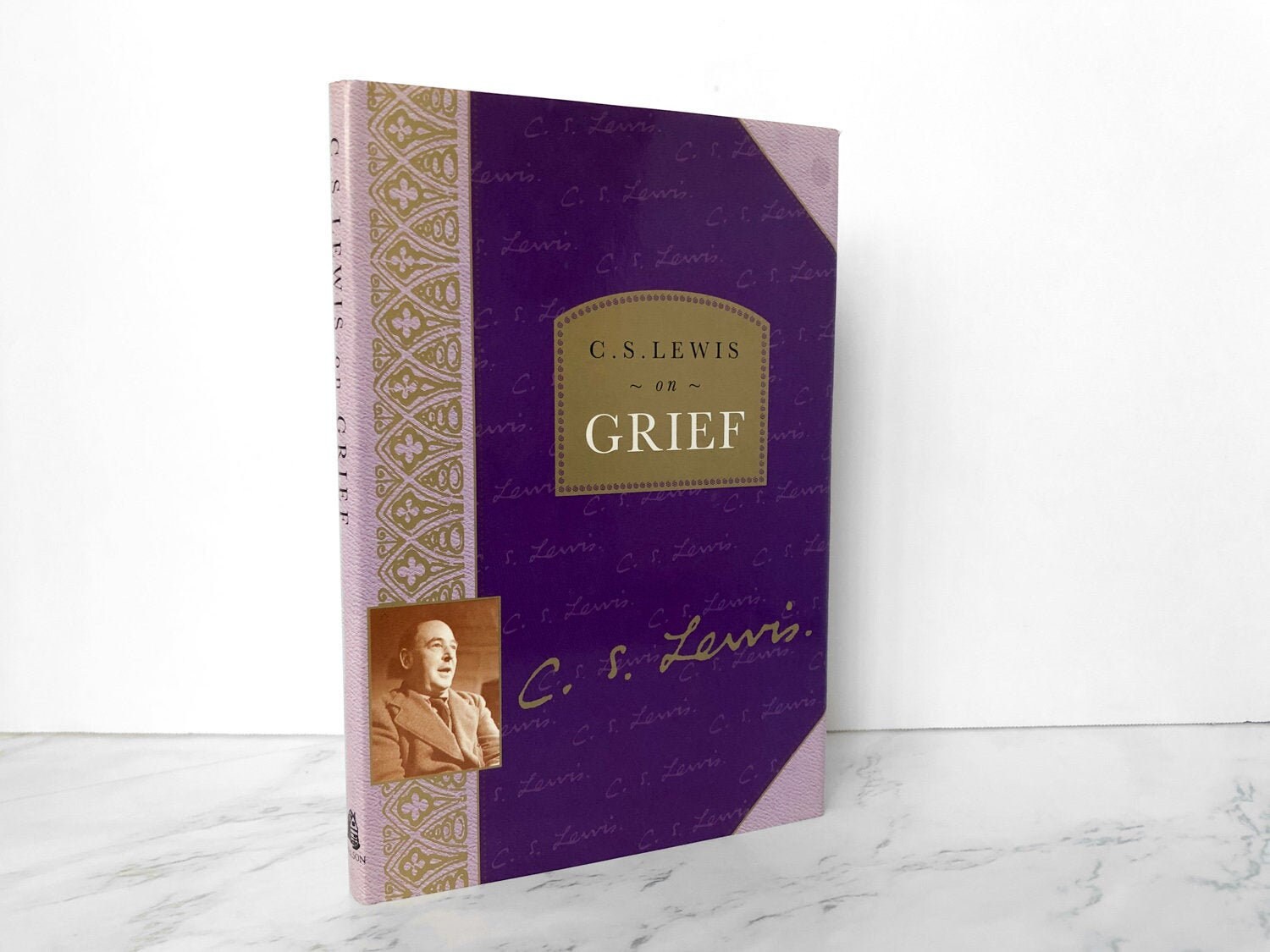

This series of nonfiction greats does not typically narrate the backstory to the classics it selects, but the circumstances of A Grief Observed are worth repeating. Indeed, some of Lewis’s best passages recall the intensity of an earlier and very passionate essay, The Four Loves: “We have seen the faces of those we know best so variously, from so many angles, in so many lights, with so many expressions – waking, sleeping, laughing, crying, eating, talking, thinking – that all the impressions crowd into our memory together and cancel out in a mere blur.” As Rowan Williams has written: “If the anguish of loss can be honestly lived in (not ‘through’), it must be with a clear recognition of the impossibility of possessing or absorbing anyone we love.” Once the reader has tuned his or her sensibility to Lewis’s wavelength, this unsentimental, even bracing, account of one man’s dialogue with despair becomes both compelling and consoling in several intriguing ways not necessarily associated with death. Some of Lewis’s exclamations are raw and modern. Grief is like a long valley, a winding valley where any bend may reveal a totally new landscape.”Ī Grief Observed is an unsettling book for a secular age, plunging the reader, as it does, into allusions to St Augustine, considerations of heaven and eternity, coupled with some intense, self-analytical discussions about separation, solitude and Christian suffering. There is something to be chronicled every day. It needs not a map but a history, and if I don’t stop writing that history at some arbitrary point, there’s no reason why I should ever stop. Much of his text is quasi-theological other parts have a self-help flavour that quickly morphs into lyricism: “Sorrow,” instructs Lewis, “turns out to be not a state but a process. For a believer, writes Lewis, bitterly, “the conclusion I dread is not ‘so there’s no God after all’, but ‘so this is what God’s really like. In good times of happiness and security, you might have no sense of needing any consolation and might even assume that God will not be available when he is needed.

This unsentimental, even bracing, account of one man’s dialogue with despair is both compelling and consolingĮven a confused non-believer can appreciate the deep sense of betrayal here.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)